Pursuing Stillness

Last weekend’s mindfulness retreat helped me to reconnect with my inner wisdom and made me more determined than ever to practice stillness in the midst of our global storm

“Why are you here?” the facilitator asked in the opening session of the three-day online mindfulness retreat. I’ve done several silent retreats over the years. They almost always start this way. Yet I was not prepared for the question. Practically, I was there to fulfill a requirement for my certification as a mindfulness teacher. We’re supposed to do at least three silent retreats at different stages of the process. This was my third required retreat.

It was not, however, the one that I had originally intended to attend. Earlier in the year I had made arrangements to attend an in-person retreat for Black, Indigenous, and other people of color at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in California. Attending that particular retreat had been a dream of mine for at least a decade. Right after I paid my last installment and bought my plane tickets, I had a family crisis that made me feel anxious about being 2500 miles away from home and out of contact for seven days. I decided not to spend my retreat battling anxiety. I cancelled and looked for closer options.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a weeklong retreat nearby that fit my needs. So I signed up for two shorter retreats: a three-day online mindfulness retreat for BIPOC and allies, and a four-day in-person silent retreat at a local Ignatian retreat center. While it wasn’t the retreat plan that I’d had in mind at the beginning of my summer, it felt like a fitting plan for my spiritual and emotional needs. I’d get to experience both the Buddhist meditation and Christian contemplation traditions that nurture me. One setting (I booked a room at the Waldorf Astoria for the online retreat) would be urban and luxurious, while the other (a Catholic retreat center) would have simple rooms surrounded by natural beauty.

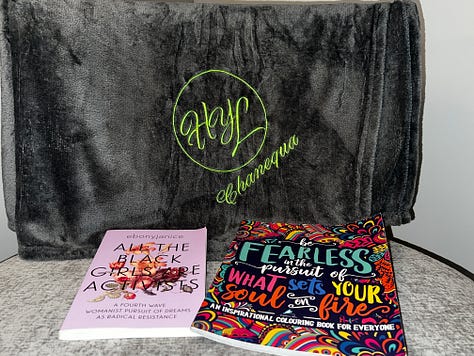

I arrived at the Waldorf on a Friday afternoon, loaded with a yoga mat, meditation cushion, and shopping bag full of food to help minimize how much I would need to interact with other people. I wanted to maintain the silence as much as possible. For three days, I stayed inside my room, venturing out between sessions to do water aerobics in the warmest pool I’ve experienced and to take advantage of the whirlpool and sauna. I put my phone on do not disturb, blocking all callers except my husband and son, who I knew would call only in the event of a real emergency. Except for the Zoom sessions for the retreat, I avoided all media, including television, music, news, social media.

Normally I don’t even read during a silent retreat. This time, though, I decided to spend time with EbonyJanice’s book, All The Black Girls Are Activists, because I needed someone to pour into me the way that I pour into others. I needed someone else’s voice to affirm the wisdom that the world tries to erase: the knowing that, for Black women living in a world that does not value our lives, pursuing health and well-being is an act of resistance. It is a form of justice.

For Black women living in a world that does not value our lives, pursuing health and well-being is an act of resistance. It is a form of justice.

Remembering and reintegrating that wisdom, it turns out, was why I was there. In our final large group dialogue, we returned to that opening question, “Why are you here?” I raised my digital hand to speak up. “I didn’t know this until this moment, but I’m here because I needed to be around people who recognize that stillness, rest, and peace are antidotes to the greed, anxiety, and hatred that are infecting our world. I needed to remember that mindfulness does not just fuel resistance; it is resistance. I know this intellectually. I write and teach about it all the time. But since November, my nervous system has been in overdrive. There is so much urgency to do something. I needed these three days to return to myself, to figure out what my path forward is in all of this.”

I am reminded of Toni Morrison’s wisdom that racism is a distraction. It tempts us to spend our time and energy fighting other people’s agendas instead of living into our own. This administration is incompetent in many ways, but it is exceptionally gifted in the arts of distraction and oppression. I have been very distracted. I needed the retreat to help me to find, take back, and keep my righteous mind, because this world keeps making me lose it.1

This is why I retreat. It reconnects me with my deepest wisdom. I’m looking forward to re-entering the silence again soon. In fact, I’m going to go ahead and schedule one for the fall.

What helps you to connect with your wisdom – with your peace – at a time when urgency and chaos tries to distance you from it? How can you embrace stillness and self-care as acts of resistance while also participating in the struggle to resist the evil of this administration? Leave a comment and join the conversation.

If you enjoyed this post, be sure to share, like, and subscribe. Help me reach my next goal of 7500 subscribers! I do a lot of my writing in coffee shops (locally owned, of course) so if you feel so moved (and are able), you can buy me a coffee. Thank you for supporting my writing!

I almost attributed this quote to Laurence Fishburne in Higher Learning, but it was actually Denzel Washington in The Great Debaters.

This resonates so deeply, especially the part about needing someone to pour into you the way you pour into others. That’s a sentence I didn’t even know I needed until I read it. In "Make It (Y)our Own," I talk about how retreat, for Black women, isn’t just recovery—it’s recalibration. Not rest after the grind, but a refusal to be shaped by it in the first place. What you said about mindfulness being resistance, not just fuel for it? Yes. That’s the reframe so many of us need right now. Thank you for naming the distraction for what it is—and for showing us what it looks like to come back home to yourself on purpose. I’m adding that fall retreat to my calendar too.

In addition to my work as a parish priest, I serve as a spiritual director in the Ignatian tradition. Most of my directees are white men. Accompanying them in discerning, naming, and seeking to resist the lures of white supremacy and patriarchy is some of my most gratifying work right now. Thank you, again, for your insights, Dr. Walker-Barnes.