Black Women Teach Us to Decolonize Our Theology

A reading guide for Christians in need of liberation from theological bondage

Throughout Black History Month and Women’s History Month, I will be doing a Black Women Teach Us series, sharing recommendations for books by Black women writers who can help us to rethink our faith, fight oppressive systems, love and heal ourselves, and imagine new worlds. I’m recommending books that have been formative for me, as well as a few newer publications that I’m excited about.

Introducing Womanist Theology

Let’s start with an introduction to womanist theology. Womanist theology takes its title from the term and definition coined by Alice Walker. Walker first used the term in a 1979 short story, “Coming Apart.” Four years later, she provided a detailed definition of the term in the preface of her book, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. The book’s publication came at the same time that the first wave of African American women were earning doctorates in theology and Biblical studies. It was also a time when many Black women and other women of color had left White-led feminist organizations over frustration with those organizations’ refusal to adequately address racism. Walker proposed womanism as a more robust and inclusive approach to life and organizing, one that centered the needs and experiences of Black women while also being committed to communal wholeness and survival. “Committed to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female. Not a separatist, except periodically, for health.”

In her essay, “Womanist Theology,” Emilie Townes writes:

Womanist theology is a form of reflection that places the religious and moral perspectives of Black women at the center of its method. Issues of class, gender (including sex, sexism, sexuality, and sexual exploitation), and race are seen as theological problems. Womanist theology takes old (traditional) religious language and symbols and gives them new (more diverse and complex) meaning.

Womanist theologians approach scripture, Christian doctrine, and church polity in the “outrageous, audacious, courageous or willful” way that Walker writes about in her definition. We ask aloud the questions that other Christians repress or struggle with silently. We talk back to scripture as well as to people in political and religious power. We face the church’s complicity with White supremacist heteropatriarchy and we investigate what that means for how the faith has been transmitted to us. We break with long-standing church traditions about what faith and leadership ought to look like. We dare suggest that Black women’s lives and writings are sacred texts that can tell us something about the nature of God and what God is doing in the world.

At a time when so many Christians have left the church because it has failed to answer their questions (or even provide space for asking), womanists point the way. There is no deconstruction without decolonization.

Facing the Tough Questions

Part of Alice Walker’s definition includes “wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered ‘good’ for one.” I have a feeling that much of womanist theology begins on church pews, where Black women and girls sit silently questioning what they are hearing from the pulpit or reading in the Bible. That’s how it was for me. Just before seminary, I found a pastor who welcomed my questions (and was asking them along with me). Most of my seminary professors were not so welcoming of my questions, save for a few women (mostly White) who assigned and recommended books where I finally realized that I was not alone in my hermeneutics of suspicion.

Much of womanist theology begins on church pews, where Black women and girls sit silently questioning what they are hearing from the pulpit or reading in the Bible.

In seminary, I encountered several books that broke me open in a good way. The first was Emilie Townes’s edited volume, A Troubling In My Soul. In seminary, we talked a lot about the question of theodicy, that is, how an all-good and all-loving God could allow for evil and suffering. In Townes’ book, foremost womanist scholars turned that question toward the church, asking, “Where is the Black church in the suffering and systemic oppression of Black people?” It was my introduction to to the work of people like Marcia Riggs, Cheryl Kirk-Duggan, M. Shawn Copeland, and Karen Baker-Fletcher. It was the book that made me realize that I am a womanist. It is one of two books that I suggest when people ask for book recommendations to help them learn about womanist theology.

The second book was Kelly Brown Douglas’s Sexuality and the Black Church. Published five years before I started seminary, it was wreaking havoc in the Black church (in a good way). I was an aspiring but cautious ally when I began seminary, afraid to risk relationships with my Black classmates at the expense of solidarity with the then-all-White LGBTQIA students. Douglas’s book – and her unapologetic boldness during a lecture at Duke and a panel discussion at a Durham Black church – gave me language and courage to stand firmly in my conviction that same-gender attraction was not a sin.

No reading list on womanist theology would be complete without the classics, written by the women who birthed the field into existence: Katie Geneva Cannon, Delores S. Williams, and Jacquelyn Grant. Their first books – Katie’s Cannon, Sisters in the Wilderness, and Black Women’s Christ, White Women’s Jesus – exemplified how Black women’s feminist consciousness destabilized traditional Christian constructs and raised questions about the nature of God, the meaning of Jesus’s salvific work, and how we as Christians are meant to live. They were the first to show us that our bondage and our liberation were deeply rooted in our God-images and that Black women’s moral agency could (and should) be utilized to correct God-images that were saddled by racism and patriarchy.

Since their initial work in the late 1980s, many others and have built upon their work. I especially appreciate the work of writers who demonstrate that womanism is not just an academic theory but rather an orientation toward life that emerges out of the lived experiences of ordinary Black women, as Monica Coleman and Yolanda Pierce do in Making a Way Out of No Way and In My Grandmother’s House, respectively. In Ecowomanism, Melanie Harris illuminates how some Black women practice earth-centered spiritualities that connection liberation and creation care. In Our Lives Matter, Pamela Lightsey challenges the heteronormativity that remains within womanism despite its acceptance of Walker’s definition of a womanist as “a woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually…sometimes loves individual men sexually and/or nonsexually.” She utilizes the concerns of Black LGBTQIA women and femmes to articulate a womanist queer theology. points out the dissonance between womanists’ bold acceptance of Walker’s definition of and the frequent heteronormativity in their scholarship.

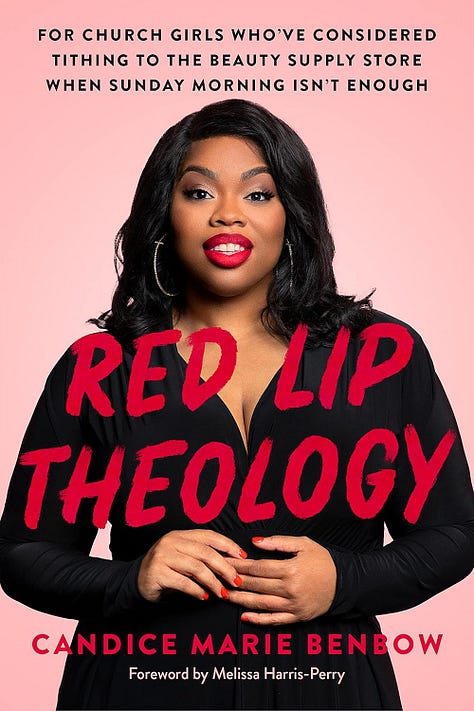

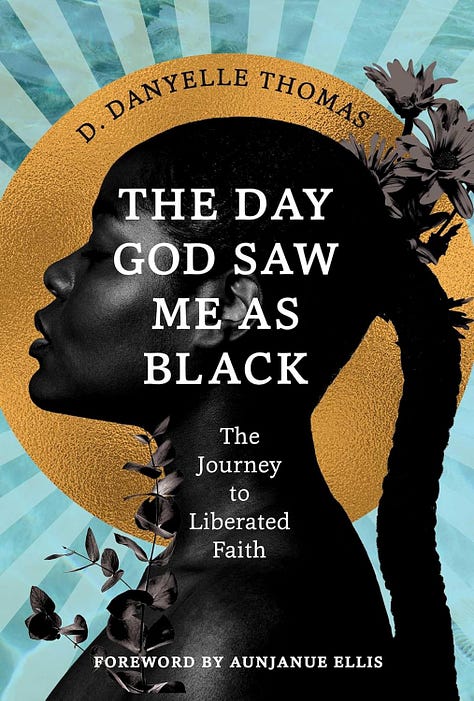

More recently, millennial womanists have been putting their own stamp on the field, with work that is body- and sex-positive, deeply engaged with popular culture, rooted in the twenty-first century movement for Black liberation, and willing to address issues of mental health. Candice Marie Benbow’s best-seller, Red Lip Theology, is one of my favorites in this category. And I’m looking forward to reading D. Danyelle Thomas’s new release, The Day God Saw Me as Black.

These books all fall within the areas of theology and ethics. And they barely scratch the surface of the incredible womanist scholarship even within those subdisciplines. Next week, I’ll continue this series with recommendations for womanist biblical interpretation and leadership.

Get these books. Purchase them from a local bookseller or from the Womanist Theology Foundations list that I’ve created at Bookshop (I’ll add each week). Borrow them from your libraries and request that they purchase them if they’re not already in the collection. Read to liberate yourself, to help liberate us all. Because God knows we need it.

Register for the Sacred Self-Care Group Study Guide

A few days ago, I sent the content for the Sacred Self-Care group study guide off to the designer! The study guide includes a detailed outline for seven sessions, each corresponding to the seven weeks in Sacred Self-Care. There are centering practices to open each session, a review of the week’s theme, and discussion prompts that help groups delve into the wisdom of the group.

So get your people together, buy your copies of Sacred Self-Care, and register your group by February 24. The week before Lent, you’ll receive a copy of the group study guide and an invitation to the live Zoom webinar with me on Easter Saturday (April 19) at noon eastern.

When I think back on my own childhood, sitting in pews and questioning Bible passages, I had a father that reinforced the practice.

My dad grew up in a family of Quakers. He was encouraged to never take anything in the Bible as actual fact, since it was all interpreted through men. He instilled this in his children.

When my daughter attended Colgate-Rochester-Crozer Divinity School she found a spiritual home in a Womanist Theology course.

I appreciate this post. Since my daughter is temporarily storing her books from CRCDS, I may need to see if some of the books you shared are here in my house.❤️

Thank you for these recommendations. Yesterday I read your Woke Creed over and over and sent it to friends. Your writing hits deep. Your language for God is a lifeline. Your work is a gift. Peace to you.